ACE 2026 - The home of global charter.

The bimonthly news publication for aviation professionals.

The bimonthly news publication for aviation professionals.

The business aviation industry benefits from continued development in aircraft specifications and such advances are much vaunted. Not long ago the first A380 was stripped for parts at the tender age of 10, but what happens to business jets, turboprops and turbine helicopters at the end of their lives? Are they scrapped, parted out, repurposed? EBAN readers have been sharing their experience and expertise relating to business aircraft as they process gently towards their retirements.

Not all aircraft are created equal – business vs commercial

When it comes to reckoning the value of old models, and whether to scrap them or not, there are two major differences between business and commercial types: cabin interiors and maintenance intervals. "But to better understand how and where aircraft go to die, we first need a bit of background on how and where airplanes live," says Channel Islands-based Avionco continuing airworthiness manager Andy Kapusi.

He explains that business aircraft enjoy a relatively low utilisation of up to 1,500 flight hours per year as opposed to between 2,500 to 4,000 for commercial airliners. As a result, components tend to wear out 50-90 per cent more slowly and maintenance intervals are predominantly calendar driven, rather than related to total aircraft hours and cycles as they are in the heavy commercial utilisation category. To ensure continued airworthiness, 'heavy' inspections will take place at least every four years, rather than within 18 months to two years as in the commercial sector, but the maintenance programmes will be just as strictly monitored.

Commercial aircraft have a useful life of on average 20 years, based on the manufacturer's 'life limits' for major or critical components; in most cases limited by the airframe, engines, landing gear and the sub-parts. Boeing gives on average a 75,000 cycle life limit to its airframes so their useful life will range from 17 to 30 years. Well-utilised airframes will have undergone numerous structural repairs for which they will bear visible scars: patch repairs comprising engineered doublers/ triplers on the primary pressure vessel as a result of years of battling the elements, a barrage of stone chips/dents, inadvertent foul play from baggage carts/tugs and other mobile service equipment.

Of course a small percentage of aircraft will last over 35 years but these are usually on life extensions and have undergone specific re-purposing; the upgrades are typically expensive but can work in the proposed future aircraft utilisation business model.

For business aircraft the useful life calculation will vary for each operator, depending on whether they fly regionally or long range. It is rare to see the business airframe 'time-ex' or reach the aircraft's life limit; business aircraft are more likely to become obsolete due to the introduction of more technologically advanced models and stricter regulations. Speed, reliability, fuel efficiency and, progressively, more environmentally-conscious features play a big role in determining when one type of aircraft surpasses another older type. While in service, these old aircraft are typically re-sold at average or above average market value, factoring in steady depreciation due to age and wear and tear. Some get parted out, the same way as their airline counterparts. However, even the so-called useful components can become obsolete and be scrapped simply because owners do not let them go in time. "Prolonged storage, particularly improper storage, can be far more damaging then rigorous utilisation, as was the case with a Boeing 707 with a full VIP interior that was parked in the Arizona desert for over 10 years," Kapusi says.

Business aircraft have specifically engineered and approved interiors; the cost of their research and development, installation and final certification is typically high to very high and can equal the purchase cost of the aircraft, whereas commercial cabins are designed to strict budgets to maximise passenger count or cargo haul capabilities. "Even the best looking first class interiors are designated as 'simple' designs," he says. And from the onset these aircraft will be cost-adjusted, with sizeable discounts provided to lease giants with massive buying power. "Simply put, you buy in bulk, you save," he says.

Business jet interiors are often purpose-built to suit individual tastes, whether it is for private owner use or for charter, and the aircraft tend to undergo full interior refurbishment and exterior colour scheme changes at every re-sale event. The redesign may also incorporate additional avionics upgrades or airframe modifications, included to meet and exceed the operational criteria required by specific regions or airports. These all represent costs that every owner wishes to recover, but which potential buyers would rather not incur.

But inevitably there comes the day when any aircraft can be classified BER – Beyond Economic Repair. Once an airframe becomes "time-ex'd", it remains for the owner to decide the fate of all remaining components.

The airframe is typically stripped and recycled for the aluminium, which is low in value and sold by the pound.

Engines are probably the most valuable component at this juncture, provided all life documents are complete and accurate. Time or cycles remaining can be transferred to another aircraft, so individual engines are quite valuable to the operator and are typically worth the overhaul price tag when set against the purchase of a new engine; overhaul costs average from 35 per cent to 50 per cent of new price and reserves, as a fixed cost, are built into operating budgets to mitigate the overhaul down time and cost. However, aircraft engines are not financially viable for indefinite over-hauls because the affiliated costs eventually exceed reasonable economic limits as more, and eventually all, core components require replacement. At this stage engines are scrapped.

The landing gear is arguably the second most valuable component and the same life document criteria apply as with engines. It can also be sold, purchased or leased for the remainder of its useful life. Landing gear does have a 'calendar' life, where time between overhaul (TBO) is another limiting factor alongside hours or cycles. Calendar limiters mean maintenance action or overhaul will be due whether the gear is utilised or not, and beyond its useful life the gear components will be scrapped.

Individual components such as primary flight controls, actuators, line replaceable units and other on condition and condition monitoring parts may be sold or purchased provided a certified engineer gives the part a bill-of-health, a green tag, which identifies the component as 'removed serviceable'. Along with a part history report, this official part certificate (8130s or Form 1s) may be required for traceability and value determination.

In summary, says Kapusi, business aircraft can potentially be parted out in the same manner as commercial airliners, but since they inherently carry a healthy remaining balance of life limits owners prefer to sell them on as serviceable aircraft. Market conditions are largely based on saturation, the total number of identical or comparable aircraft for sale, and individual subjective design preferences in terms of interior layout, colour palette, fit and finish. These drive demand for such aircraft, but in some cases the secondary market will absorb the higher time on used aircraft once costs descend to manageable levels.

"In truth, many variables govern what is considered to be the lifespan of an aircraft," he continues, "and these all have a direct impact on where and when an aircraft is considered dead. With enough time and money one can do anything, but I prefer to advise from the perspective of a cost versus benefit analysis based securely within the margins of airworthiness."

If it's not BER …

"Even at 30 years of age an aircraft still has potential," says Switzerland-based Jet Aviation key account director Marc Dusseau, who, together with OEMs and vendors, can offer a range of modifications thanks to today's well-developed technologies. He notes, however, that a number of restrictions have been introduced over the last year and more are coming into play by 2020 covering ADSB-Out, CPDLC and FANS. Operational requirements must be in line with these.

Jet Aviation MRO centres assess each aircraft individually. The market value is analysed with respect to the cost of all these upgrades compared to a sale on the pre-owned market. Whether the aircraft is operated privately or for charter will also determine the selection of upgrades in the cabin.

Those most frequently applied are cockpit avionics modifications such as an upgrade from a Pro Line 4 to 21, which comprises the latest generation of navigation systems. This reduces the obsolescence issue and also fulfils most of the 2020 avionics mandate.

Dusseau says it is risky not to replace any obsolete equipment with supported equipment, and this applies not just to the engine but the systems and parts too. If the aircraft is retained for charter then its reliability may be compromised, causing unnecessary delays and disgruntled clients.

Owners and operators will want to know what work needs doing on the aircraft based on an evaluation of the many technologies and options available. It could be possible to invest $20 million and have an aircraft that would provide nearly the same service as a $35 million investment in a new aircraft. For them the key message is that an aircraft of 30 years should not automatically be scrapped as there are other options to be considered.

If an aircraft is well looked after and maintained it could operate beyond even 35-40 years. The scheduled maintenance events, the C or D checks depending on aircraft type, give Jet Aviation the opportunity to establish, and advise the owner/ operator on, what the next step should be. It enables the company to anticipate what work needs to be done, whether it's an optional upgrade, the removal of obsolete equipment or fitting the latest standard in cabin comfort.

In the case of an aircraft being BER, Jet Aviation has various partners who facilitate the end-of-life process, which tends to be relatively quick and mainly requires the de-registry of the aircraft from its local registration. It is then dismantled part by part, each being individually re-certified and listed on an inventory market. In a worst case scenario the whole aircraft could be scrapped and sold for the weight of its metal.

Market demand is a key influence

What happens to an old aircraft depends largely on market demand at any given time and at Irish operator ASL Aviation Holdings, whose jet and turboprop business fleet comprises mainly ATR 72s and Boeing 737s, if an ageing model cannot be placed with a suitable lessee, or operated for a customer, it is parked or removed from service. Storage depends on its financial status, particularly if it is a newer, higher valued model, and an expectation that demand would return to the market. Chief executive, fleet and leasing, Dave Andrew says: "There are many specialised storage facilities around the world, usually sited in dry stable climatic environments such as the deserts of the USA where possible corrosion and other storage impacts are reduced."

Alternatively an aircraft can be sold, providing there is a market, or parted out. The part out option is calculated against the expected return from the sale of the parts versus remaining book value. "There is always a need for parts," he adds. "The size of the demand is dependent on the size and age of the active fleet, whether the model is still in production and the availability and costs associated with maintaining the removed part. For example, a part life remaining engine would have a varying value dependent on expected overhaul and repair costs, the availability of shop capacity and events that may drive unexpected or unplanned demand such as a manufacturer or airworthiness authority directive."

The decision to permanently ground an aircraft is based on several contributory factors: market demand, or lack thereof; age and maintenance status; and in particular associated expected costs of required maintenance versus the ability to recover the maintenance investment in the future. Andrew reckons the two main drivers here are obsolescence due to replacement by newer models, and limited second stage life of a relatively new model due to there being a very limited operator base or an existing operator pool that prefers to only operate new aircraft.

Africa is no longer a dumping ground

"Fifteen years or so ago, Africa was a dying ground, even a dumping ground, for old aircraft," says Andre Coetzee, CEO and chief pilot of South Africa-based operator Henley Air. "This was especially the case for earlier generation airliners, some of which were no longer allowed to operate in Europe and found favour here within the lesser states." He has seen this not only with the Henley Air fleet, but with general aviation aircraft and flight school aircraft too. "Ageing of the fleet is quite substantial."

The GCAA in the UAE will not allow the import of any aircraft older than 20 years says Abu Dhabi-based GI Aviation general manager Captain Patrick Gordon: "If the aircraft is over 20, and already in the country, it can continue to be operated, but there are no imports of oldies." And as other countries adopt similar regulations he suggests it will be necessary to look into how to take care of all the old, excess aluminium flying around.

When the recession hit around 2008 there was a rush in Africa to import the hundreds of helicopters being off-loaded by owners around the world, specifically Robinsons, but things have quietened down now. "I can't recall the last time I saw a brand new R22 for instance," says Coetzee, "and those used to be hot cakes a few years ago." He notes a swing towards the new Bell 505, with five or six of them arriving in South Africa recently at more or less the same time. But there remains an influx of second hand machines from around the world, to be cleaned up and readied for service.

From his own experience, typical acquisitions are a delicate balance of where it is in its useful life, time remaining on the components, the engine and so on. "Henley Air is investing heavily in the Bell 222s," he adds. "We look to acquire them at a very good price and then balance that with the availability of spares and engines to extend the useful life for another ten years maximum; we don't see it going beyond that. We find that they all have a finite life based on the lack of support from Bell for its legacy lines. They want to sell the new machines and not really support the old ladies any longer."

As an experienced operator of Bell helicopters, Henley Air has considered expanding into the 230 series, because the 222 and 230 models have worked well for the company so far, as have the 430s, although there are fewer of these. Taking into account the normal attrition that occurs over time, Coetzee says the ones that are left aren't well-supported. He would look to utilise the last few 230s in the world, and then move on to the 430s.

He has seen the effect of age-proofing on aircraft that have been well-looked after and hangared for many years. But some of the helicopters the company has received have really been abused: "They have been sitting in the sun in the Californian desert or outside a hangar for years on end and a lot of TLC is required. Henley Air has a fair inventory of spares and stock and has been able to turn these aircraft around and clean them up quite nicely."

However some are simply beyond economical repair or reintroduction to service. These are disassembled as much as possible in order to sustain the rest of the fleet. One such aircraft was more or less gutted and had no value, so instead was converted into a Bell 222 simulator for in-house and third party training prospects. "Rather than trashing it and selling the scrap metal to an aluminium dealer, we turned it into a beautiful simulator," he recalls.

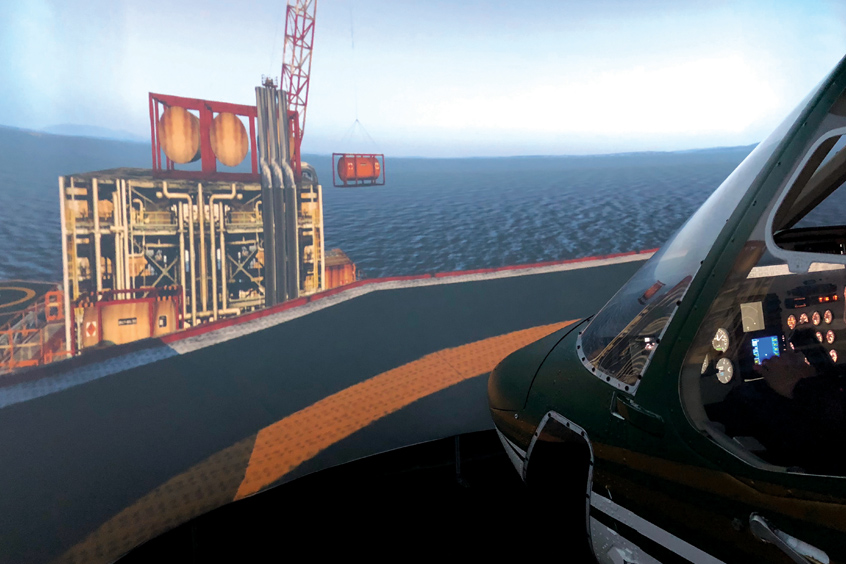

The beginning of a simulator's life

Austria's Axis Flight Training Systems makes full flight simulators for turboprop, regional and business jet pilot training. CEO Dr Christian Theuermann explains that the first step is for Axis to contact aircraft boneyards to request images of the parts needed for the simulator to be manufactured. The company prefers to take cockpits that still have seats, that are lined and have intact windows. They also need to be complete up until the circuit breaker wall, and should include the throttle quadrant and pedals. "It is important to us that the cockpit is as close to the original as possible, to give pilots and cadets the most realistic experience during their training," he says. Once all these factors have been considered purchase negotiations begin.

Next, the company uses a laser to take accurate measurements of the cockpit in order to build the hardware and to produce a 3D model. The cockpit is then thoroughly cleaned and dismantled, everything is reviewed and as much as possible is retained. Where it becomes necessary to buy replacement parts, Axis tries to do so from the OEM. The parts kept are categorised and then fully tested, and replacement parts also undergo strict quality control and testing.

The next stage requires the outer part of the nose section to be cut to size, removing the back for access and the underneath to create a flat surface. It is then cleaned, sand-blasted and painted black to minimise reflection from the mirror. The whole thing is then put together again with original parts and any new OEM parts that were ordered. "Then the real fun begins," says Theuermann, "combining the hardware and the software we have developed to ensure we replicate the exact cockpit conditions of the aircraft simulator type we're manufacturing."

A 50-year-old Twin Comanche

There is a certain 50-year-old lady who refuses to go quietly. CC Air Service (CCAS) pilot Cristian Reinhardt from Germany is flying an old Twin Comanche so as to get it a new airworthiness review certification. The original owner died a few months ago but even before then he had been flying his other aircraft, a Cessna 440, much more than the Piper. Thus it was in really good shape when CCAS acquired it; it had always been hangared and cleaned, and looked as though it had flown far fewer than 50 years.

"We had to make some changes to it. It is 50 years old but it has only 950 flying hours on it," says Reinhardt. It had only been used for very short flights but had been maintained in such a way that it could be ready to fly at any time. The company is looking to sell it and has several interested parties that are flying VFR rather than IFR. Reinhardt says: "It is a cheap aircraft to fly, parts and fuel are always available, and there are around eight or nine Twin Comanches in southern Germany so there are still people around that know how to maintain them."

Fun and games

Captain Ayman Osman of Khartoum-based Green Flag Aviation used to fly Russian Antonovs around the Sudan, and while most have been sold on for parts or training there is still some demand for cargo business, especially of livestock, and the occasional Umbra and Hajj passenger flight.

He has clients in China, Kazakhstan and Sudan who want the engines of Antonov 12s to use for ground and industrial purposes, not for flying. Sometimes the old models are scrapped, but they do contain certain materials that can be used by factories, possibly for turbine production, such as iron, aluminium and copper.

He has also received requests from university aeronautical engineering departments, most of them in Bangladesh and Senegal, that want the old aircraft for student training. But he recalls that some models have been converted to restaurants, caravans and even accommodation. Latvia-based Baltic Jet director Captain Boris Matveyev adds that some are taken to aviation museums, or used as children's' education resources, as at Riga airport.

In the ex-Soviet republics there are a lot of Tupolevs that have become dedicated monuments to aviation traditions, adds flight operations director Euten Tatu at C&I Corporation in Romania. A good number of ex-military aircraft have been transformed into coffee bars and one is even a summer house. He says young architects are interested in reviving old planes: "Some of these are located in the middle of forests so I have no idea how they were carried there," he says.

He has also seen helicopter-derived power plants used to drive pumps for oil and gas. Specific engines such as those used on Puma helicopters are good for this, and they can also be used to propel boats or in wind tunnels. The movie industry uses old aircraft for special effects, at Chisinau airport in Moldova passengers are welcomed by a discarded Tupolev on a plinth and at Marseille Provence airport a Eurocopter EC130 is preserved on a roundabout next to the terminal.